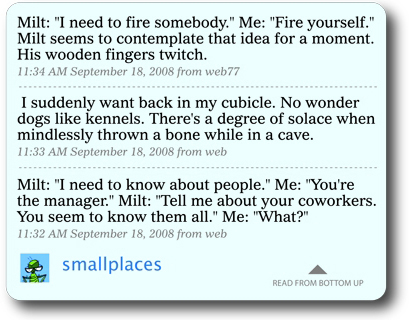

Original gif used Small Places

ESSAY: THE CONTINUING TALE OF THE VIRAL TWITTER NOVEL ‘SMALL PLACES’

Small Places was launched on April 25, 2008 at 9:38 p.m. with a cluster of tweets. By the time it ended on March 8, 2010 at around 30,000 words, the Twitter novel had gone viral across the globe, reaching a height of No. 73 in global Twitter rankings. No marketing or press releases were involved. Only a few blog posts and the first 358 tweets collected on The Nervous Breakdown, an L.A. literary collective turned lit-journal site.

In an article posted on February 25, 2015, five years after the final tweet of Small Places, Quirk Books was again listing it as one of ten literary social media accounts for bookish people to follow. On April 18, 2016, Arielle Hubbard, a student at the University of Versailles outside of Paris, contacted me about the passive consumption of literature in regards to twitterature. The term had since been coined in regards to a portmanteau of Twitter and literature, which is a literary use of microblogging. Of course these Twitter-related literary terms weren’t around in any form between 2008-2010. The phenomena of viral literature in any form seems rare, and the idea of yet another university student studying the idea of twitterature in 2016 was astounding, a testament to the power of experimentation and words, in this case, words typed from two different living rooms, a news room, and a coffeehouse, all in Bakersfield, California.

SMALL PLACES IN ACADEMIA: IS TWITTERATURE LEGITIMATE? THE UNIVERSITY OF VERSAILLES CASE STUDY

Arielle Hubbard, a graduate student from the University of Versailles “Culture and Communications” program, wrote in an April 2016 letter, “While reading Small Places, I was drawn in by the humor (the wacky names!) and the crisp brevity. Not knowing what I would encounter beginning this project, I was delighted to discover a strong narrative and veritable accomplished piece of short fiction.”

We soon exchanged a few emails and she sent a list of questions. While I won’t post all of my answers to her here, I will share one note in regard to her suggesting she would defend twitterature from a French point of view because she saw how many in France felt a lack of legitimacy. Of course, if you look at the list at the end of this bit of writing you’ll see responses to twitterature since 2009 or so from the leading newspapers in the world on multiple continents (The Christian Science Monitor was still in print in those days), as well as academic responses representing countries like Turkey, Qatar and Italy.

My response to Hubbard: “I agree about how internet literature lacks legitimacy in the eyes of some. Who are these people? A mix of academics, publishers, and writers in general, people with more traditional mindsets, the status quo, who think literature has to be packaged a certain way with certain gatekeepers in place? I assume that’s who the critics are. Pretentious literary zealots who want to guard change, who might quite possibly fear changes in storytelling that might come from the bottom up, rather than trickling down from the top.

“Yet, more and more, I’ve spoken to college English professors (and let’s not forget publishers have printed lots from social media, and journalism obviously integrated before publishing) who are delving into internet literature as a viable means of literature — whatever that means, right? (think about J.K. Rowling’s collected tweets. Someone would buy a memoir of those in ten years).

“We can define very broadly or very specifically here what internet literature even is. More and more, journals are turning to online only, or at least placing fiction, nonfiction, poetry and essays in print and online. The value of internet publishing here is in the audience, in the interlinking, in the potential longevity, right? That’s one definition of online literature: any literature that is on the internet and can include any kind of experimentation on any platform (2018 sidenote: some journals are asking for micro-fiction on the level of only a few dozen, or hundreds of words. Does this further legitimize Twitterature?).

“I think experimental literature using social media as a platform (though I can think of others) is where the legitimacy question continues to come up at least where I’m concerned. There are few if any gatekeepers, few social media literature publishers who are considered credible (that would take some defining as well).

“Strangely, when well-known writers experiment with social-media-platform flash or a combined social-media-platform flash-serialized fiction they seem to have a sort of auto-legitimacy because of who they are. Kind of like walking into a major chain bookstore and seeing David Duchovny (famous American actor) suddenly has his own workk on the ‘new fiction’ shelf. WHY? He’s a damn actor! We all know why. Money, popularity, his built-in audience. Audiences do legitimize literature, don’t they? If Duchovny wrote a Twitter novel, we could hedge enormous bets that suddenly more of the literary world would legitimize such art and storytelling techniques.

“I was experimenting with this type of social-media-platform literature just after Twitter hit the market in 2007, and while many news outlets have spread the word of experimental literature fusing technology and storytelling, at first few lit-based news sources (or literature classes) discussed this strange literary trend. It’s only because time has passed that literary history is taking a look at the question of legitimacy more deeply. Time does this. We look at the past through the ever-changing prism of the present. I read that once in a history book, and since the art of storytelling, especially that which captures a culture, or an era, and is a form of social commentary, has been scrutinized for thousands of years, it makes sense that Small Places would be frowned at with a lens of presentness.

“But what is Small Places? A Twitter novel? Cell phone novel? A fragmented story? Flash fiction? A mockery? An experiment that resembles the words scrawled in walls in Jeff Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy (2014) that speak of organic words, living and breathing, yet dead, a residue for future generations to ponder, that lead the reader into deeper mysteries about the future of everything, and the dark past and present surrounding it all?

“If we think how literature, like history, builds on itself, then it makes sense that when Twitter started, how Twitter was partially marketed as a “cell phone technology,” not that you couldn’t blog or post pics via cell phones in the days just prior to the usage of the term smart phones, and touch screens, that a literary use of Twitter was an expansion on the idea of Japanese cell phone novels, which were actually selling for high dollars. Not that I could read Japanese, but I loved the idea, and I loved the idea of people receiving bits of stories to their cell phones. It was such a new idea, and really was what helped motivate me to keep up with the project after several lapses. Nowadays Twitter isn’t considered a nouveau smart phone technology. No one is going to set up their Twitter account and smart phone to “receive” a story in the middle of their corporate board meeting, at least not in the numbers I had in 2008 or 2009 when the readers of Small Places were half interested in the story and half interested in the technology itself that was so new. Stories could be beamed to their phones, and especially one that mocked the corporate elite like Dilbert or Office Space.

“Still, those literary gatekeepers weren’t there… (Or weren’t watching anyway).

“And I should say that you should write Bovary via Twitter, re-imagined [Hubbard mentions in her question/comment to me]. How lovely would that be? Would you tweet it in English or in French? I recommend you try to get funding for the project in some way. Funding for projects and associations with institutions legitimizes literary experimentation at a much quicker pace. I’ve been working on other aspects of my career, and is really why I never finished by So Long project on Ello [I now consider it finished]. It’s really an artform I shouldn’t continue to do unless I’m linked to an academic writing program that supports such experimental literature.”

THE GERM FOR SMALL PLACES AND TWEET CLUSTERS

It was 2007. I recall living in a house on Forrest Street in Bakersfield, just down the street from the Simon Sundale mansion setting in my Lords of Bakersfield novel. I’d been walking to work a lot, a high-tech automation company in the downtown area, dodging the homeless pissing on walls. There the sidewalks seemed a grimier grey than in other areas, the streets, dirtier. I hated my corporate cubicle job. The people were hollow, like shades from Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night (1932).

I’d just joined Twitter and recalled reading several Japanese cell-phone novels. The idea of a Twitter novel quickly haunted me. I wondered if I could build an audience interested in not just getting web updates of short literary bursts of a novel, but getting cell-phone updates (notice the outdated terminology). Twitter users could receive these updates anywhere: in a car, in an elevator, on a subway, while at an amusement park or in a restaurant anywhere in the world.

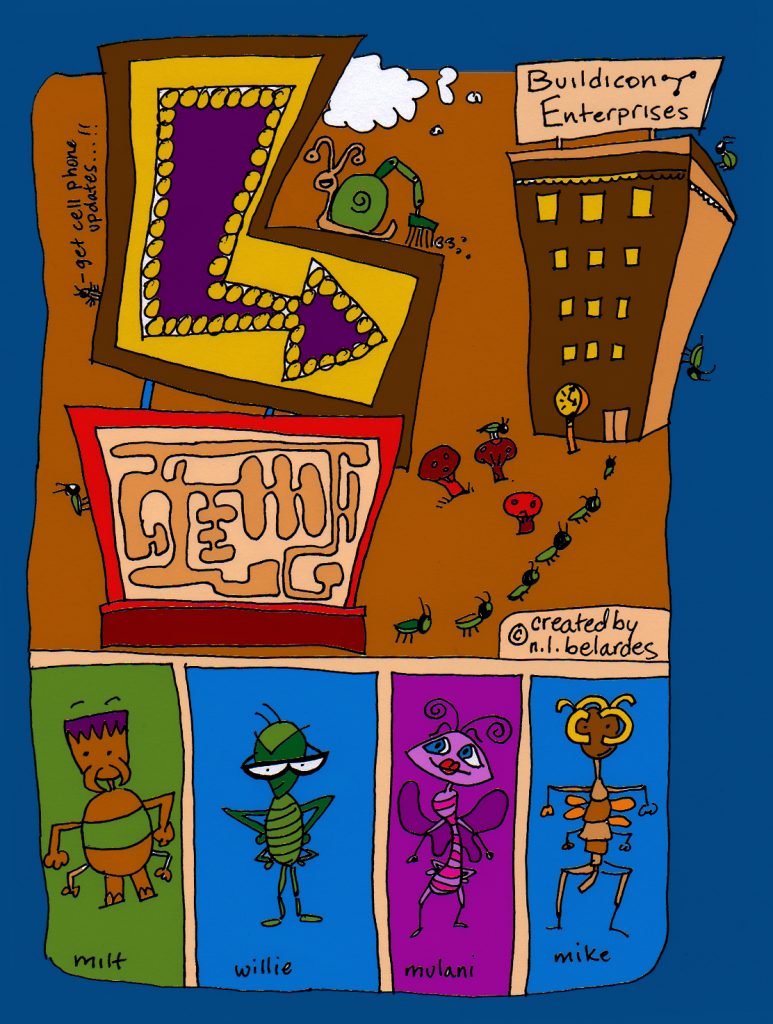

Original artwork used in a now defunct blog article

A Brazilian journalist for Folha asked how I came up with the idea. I mentioned my early thought process and what I told myself:

Don’t write a novel using Twitter, but mold a novel, transform a novel using Twitter. Twitter isn’t a scratch pad. A writer should have a plan, and so should either use a completed manuscript, or a portion. The line-by-line rebuilding of the manuscript should be challenge enough. There should be lots of note-taking, forethought, and not just random phrases thrown at readers.

I also noticed before posting any of Small Places that a possible Twitter audience shouldn’t just be whoever I thought readers were. The story itself, I thought, should lean heavily on the side of what Twitter users mainly were at the time: corporate workers, business people into networking, CEOs and plain-old office workers. I mean why not? It was so new, I thought some Twitter users might think the novel was REALLY HAPPENING.

I had about two thirds of a manuscript titled “Cubicles” that I had written around 2004. I considered it like Office Space but with a bit of life’s philosophy intertwined. The American version of The Office wasn’t even around yet.

I figured, “Now there’s something that people might read on a cell phone. It’s almost already tailor-made!” So I started rewriting a chapter at a time. I blocked it out in tweetable mini-scenes. I also decided that “Cubicles” by itself wasn’t captivating enough. I added more comedy and new themes like the main character’s obsession with bugs. I started shaping it for the small world that Twitter is: limited, compartmentalized and filled with small places. I then changed the title to Small Places and started tweeting it on April 25, 2008.

When I was interviewed by José Manuel Blanco a Spanish journalist for Hoja de Router and Teknautas, he asked how I prepared to write the tweets. “The process was very organic. Sometimes I made up the tweets right before I sent them. Usually in little bunches of 2-4. I ripped apart “Cubicles,” re-wrote, added to, threw away, kicked, tore, and really molded it into something new. That was the germ of the story, which was loosely based on an office where I had worked, the strange people who inhabited its cubicles, and the lover I had while employed there. This organic process took two years. I took several lengthy breaks. When I got to the final fifty tweets I went to a coffeehouse and wrote rough drafts for them. Still, I revised and added to as I sent them a few at a time to end the novel.”

Artwork from failed proposal to see Small Places in print

“Keep in mind,” I reminded the Brazilian journalist. “Many people have been following the story all along, or are caught up with the story. That means, it’s easy for them to follow and read. Once again, the beauty is in the cell phone functionality. People can be walking down the street and get the story’s updates. In all there’s 950 tweets of Small Places. People don’t have to scroll back very far to find the beginning.”

HOW DID SMALL PLACES GO VIRAL?

But how did Small Places go viral? Was the novel just popular? Interesting story? Maybe both. Maybe there came a further buzz as others tried to do the same by posting their own Twitterature. Some saw that I wasn’t doing any marketing and launched PR campaigns. One in particular received backlash from my supporters for claiming he was the first. I sat back and watched, and sometimes lost interest in even tweeting my own Twitter novel. Wasn’t like I monetized it. Still, I came back to the story time and again. I had to finish what I started. And as I went along, more and more journalists around the world grew interested. Not to mention, once completed, the interest flared up in other parts of the world. From America to England to Brazil to Argentina to Spain to Italy and so on.

In the end I think the viral nature of my Twitter novel came out of the origin of Small Places. There were many journalists on Twitter, and not many writers, and hardly anyone attempting Twitterature (It wasn’t even called Twitterature). I guess when you’re one of the originators too, word is going to simply get around. And word still gets around Even now in 2018 (as I update this I’ve found an academic essay and two new tech-literature articles pubbed this year. I don’t even know who keeps up or who started the Twitterature Wikipedia).

WHAT ELSE?

Either way, since finishing Small Places I’ve dabbled in experimental fiction on Ello, and though I wanted to write a follow-up Twitter novel, Bumblesquare, it never materialized and likely won’t. In the end I’m really happy with what’s happened with Small Places, especially when it was used in the curriculum of a course at LaSalle College, Montreal, or when I heard about a professor (who I don’t know) scrawling the title on a white board during a literature course an acquaintance was taking at Portland State.

In retrospect, had I known Small Places would ever be thought of as a part of literary history I would have perhaps considered my tweets more carefully before I hit ‘send’. The world however was different then. People were eager for the tweets, and when I was in the right mood, I’d send them.

Bizarre video render from Second Life courtesy of Wishfarmers circa Feb, 2010

MINI Q & A From Discussion With Journalist José Manuel Blanco:

Blanco: Was the tweet format a problem in writing?

Me: Literature is about form. Anyone can write a lump of prose and call it a story. Just gather all your text messages and emails for a year. That’s a story. Learning how to write fiction is about learning how to adapt your ideas to form. Most fiction writers are trying new constructs all the time, sometimes varying between each and every story or novel. This has been an age-old process since cave painting.

Blanco: Did you write the story before tweeting it or was it at the same time?

Me: The writing was very organic. Though I had a germ of a story I worked from at first, it quickly took a life of its own. Often I was coming up with the tweets as I sent them. Very rarely did I prepare story tweets ahead of time. And this is a problem I see with so many Twitter novels. So many are pre-written. And that’s really not using Twitter as an experimental platform but rather as cheap promotion.

Blanco: How much time did you spend creating tweets?

Me: Usually only minutes. I was incrementally building story arcs, and this was over two years, so it wasn’t like I had to spend hours each day on tweets.

Blanco: Did you schedule them, publish them by hand every day…?

Me: By hand. I still don’t ever schedule tweets. Why be a robot?

Original artwork used in Small Places

Blanco: What’s your conclusion about the experience?

Me: Small Places was the first original Twitter novel in the world. To have shared experimental literature with so many who appreciated the story was a wonderful experience. In the world of literature I’ve built upon the body of experimental prose in a logical continuance of what Japanese writers have done with cell phone novels (and of course I have also built upon a vast history of ‘fragmented’ novels). In regards to cell phone novels that preceded Small Places, Twitter was different in 2008 than today. More people received updates on their phones. There were no touch screens, just all these crazy buttons on our phones. Nowadays the artifact of the story is its existence on Twitter itself, not as tweet bundles that zoomed into phones. You can’t see people in their offices, their phones buzzing with story updates, laughing, because they were reading such corporate irony while in their own corporate meetings. I laughed a lot then too, at the irony of it all, because really it was quite the mockery of corporate culture. But now we have these tombstones on social media. Small Places is another one of those.

Blanco: Would you do it again?

Me: Of course. I am currently experimenting with another social media platform. On Ello I have been writing the story, So Long, about a Chinese-American artist who lives in a world where she and her friends pay more attention to augmented reality games than they do life. I am working with artist Siyi Chen who is illustrating the tale. Ello offers a new media for literary experimentation and publishing. The problems are similar. Time. Money. Motivation [project completed].

Blanco: Which tips would you give to a author who wants to publish a novel, short story… on Twitter?

Me: Be organic. Don’t cheapen the world of literature by just chopping up a short story or novel and tweeting it. You will be wasting your time and your prose. Find a unique way to be organic with the medium. Build upon what’s already been tried. Maybe your creative energy will find a new way to utilize social media. And if you’re not treading new ground, don’t do it. Use more traditional publishing methods.

Important Twitterature Links:

• “Small Places” (by Nicholas Belardes)

Twitter novel resources

• “Twitter Novel In the Twitterverse” (The Nervous Breakdown) Read the first 358 tweets. Contact Nicholas Belardes if you’d like a list with time stamps (Twitter has deleted the first portion of Small Places). *This link doesn’t appear to be working, so contact me and I can send you the tweets with original timestamps)

“Twitterature” (Wikipedia)

• “The Never-ending Curiosity of the Twitter Novel” (Essay by Nicholas Belardes)

• “Twittérature” (Thierry Crouzet)

Small Places in News Articles

• “Novel By Tweet” (Christian Science Monitor)

• “A Bug’s Life on Twitter” (Social Media World)

• “Twitter proves to be a page-turner” (U.K. Guardian)

• “Phillip Pullman’s latest literary endeavor: the Twitter tale of Jeffrey the housefly” (Telegraph)

• “Keep It Short: In the Twitterverse, the ego generation and novel writing meet, 140 characters at a time” (Metroactive/The Bohemian)

• “Literatura en Twitter: Narrativa en 140” (El Litoral)

• “Marca un poema o tuitéalo: La relación entre literatura y nuevas tecnologías plantea un interesante debate” (El País)

• “Peter Pan, Pinocchio, Piccolo Principe: riscriviamo tre favole in forma di tweet” (Repubblica)

• “The fusion of literature and social media” (AL)

• “Kisah Jeffrey Si Lalat, Di Twitter Berseri Novelis Philip Pullman” (Detik)

• “The Latest Trend in Literature? Twitter Fiction” (Mental Floss)

• “Writing a novel? Just tweet it” (Reuters)

• “An Abundance of Twitterature” (Publishing Addict)

• “App-tacular: Writing on Phones, Smart Phones, and Tablets” (Lit Reactor)

• “A novel, in 140 letters” (The Indian Express)

• “Twitter as a new medium” (Publetariat)

• “Twitter kan förändra vårt sätt att berätta” (Svenska Dagbladet)

• “War and tweets: A push toward publishing 140 tweets at a time” (Colorado Springs Independent)

• “Cómo escribir un libro a base de tuits y no morir en el intento” (Hoja de Router)

• “Twitter novels: when will they be the next big thing?” (Disassociated)

• “Man Claims To Be First Tweet Novelist, Is Wrong” (The L Magazine)

• “Come i social media stanno cambiando il romanzo” (Wired)

• “Marketing briefs” (The National)

• “The romantweet story of Lucy and I” (Alessandro Tinchini Blog)

• “Nuevos géneros literarios que desconocías: desde la ‘novela tweet’ a la poesía kinética” (TicBeat)

• “The new media era of literature: The media itself is its message” (United Daily News)

• “Could Insta Novels Be the Digital Innovation that Gets You to Read More?” (Vogue)

Small Places in Academia

• “Specifics of the Twitter micro fiction novel ‘Small Places’ by Nicholas Belardes and other genres of digital literature in social media” by Filip Pikula, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava, Slovakia *NOTE: click on PREHLIADAT to see the paper in full and in English.

• “Digital Literature in the Contemporary Society: Looking at Twitterature Through the First Twitter Novel, Small Places by Nicholas Belardes” by Carmen Bozga, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

• “The World of Twitterature: An ‘unessay'” (Tweet-form essay on Twitterature for St. Johns University “English in the Digital Age” course).

• “How Recent Trends Shape Literature,” Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2016 3rd International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities, Ankara University, Turkey; Abstract by Ercan Gürova

• “Dai classici letterari a Twitter: alcuni esempi di riscrittura,” Claudia Cao, University of Cagliari, Dipartimento di Filologie e Letterature Moderne, Sardinia, Italy (Between Vol. IV)

• “Writing for Digital Spaces: Form and Constraint in Online Storytelling,” Abstract by Sam Meekings, Lecturer in Writing and Rhetoric at Qatar University

* This essay and related links were originally published on Aug. 31, 2016 and last updated on Feb. 4, 2020.